Poisson Example 2D#

Author: Cian Wilson

Description#

As a reminder, in this case we are seeking the approximate solution to

in a unit square, \(\Omega=[0,1]\times[0,1]\), imposing the boundary conditions

The analytical solution to this problem is \(T(x,y) = \exp\left(x+\tfrac{y}{2}\right)\).

Parallel Scaling#

In the previous notebook we tested that the error in our implementation of a Poisson problem in two-dimensions converged as the number of elements or the polynomial degree increased - a key feature of any numerical scheme. Another important property of a numerical implementation, particularly in greater than one-dimension, is that they can scale in parallel. So-called strong scaling means that, as more computer processors are used, the time the calculation takes, known as the simulation wall time, decreases. (The alternative, weak scaling means that the wall time ideally stays the same if the number of elements is increased proportionally to the number of processors.)

Here we perform strong scaling tests on our function solve_poisson_2d from notebooks/02_background/2.3b_poisson_2d.ipynb.

Preamble#

We start by loading all the modules and functions we will require, including test_plot_convergence from python/background/poisson_2d_tests.py, which was automatically created at the end of notebooks/02_background/2.3c_poisson_2d_tests.ipynb.

import sys, os

basedir = ''

if "__file__" in globals(): basedir = os.path.dirname(__file__)

path = os.path.join(basedir, os.path.pardir, os.path.pardir, 'python')

sys.path.append(path)

import utils.ipp

from background.poisson_2d_tests import test_plot_convergence

import matplotlib.pyplot as pl

import pathlib

output_folder = pathlib.Path(os.path.join(basedir, "output"))

output_folder.mkdir(exist_ok=True, parents=True)

Implementation#

We perform the strong parallel scaling test using a utility function (profile_parallel from python/utils/ipp.py) that loops over a list of the number of processors calling our function for a given number of elements, ne, and polynomial order p. It runs our function solve_poisson_2d a specified number of times and evaluates and returns the time taken for each of a number of requested steps.

# the list of the number of processors we will use

nprocs_scale = [1, 2, 4]

# the number of elements to solve the problem on

ne = 128

# the polynomial degree of our temperature field

p = 1

# perform the calculation a set number of times

number = 1

# We are interested in the time to create the mesh,

# declare the function spaces, assemble the problem and solve it.

# From our implementation in `solve_poisson_2d` it is also

# possible to request the time to declare the Dirichlet and

# Neumann boundary conditions and the forms.

steps = [

'Mesh', 'Function spaces',

'Assemble', 'Solve',

]

# declare a dictionary to store the times each step takes

maxtimes = {}

Direct#

To start with we test the scaling with the default solver options, which is a direct LU decomposition using the MUMPS library implementation.

maxtimes['Direct'] = utils.ipp.profile_parallel(nprocs_scale, steps, path,

'background.poisson_2d', 'solve_poisson_2d',

ne, p, number=number,

output_filename=output_folder / '2d_poisson_scaling_direct.png')

=========================

1 2 4

Mesh 0.03 0.03 0.06

Function spaces 0.01 0.01 0

Assemble 0.01 0.01 0.01

Solve 0.08 0.08 0.09

=========================

*********** profiling figure in output/2d_poisson_scaling_direct.png

In the scaling test “speed up” is defined as the wall time on a given number of processors divided by the wall time on the smallest number of processors. Ideally this should increase linearly with the number of processors with slope 1. Such ideal scaling is rarely realized due to factors like the increasing costs of communication between processors but the behavior of the scaling test will also strongly depend on the computational resources available on the machine where this notebook is run. In particular when the website is generated it has to run as quickly as possible on github, hence we limit our requested numbers of processors, size of the problem (ne and p) and number of calculations to average over (number) in the default setup of this notebook.

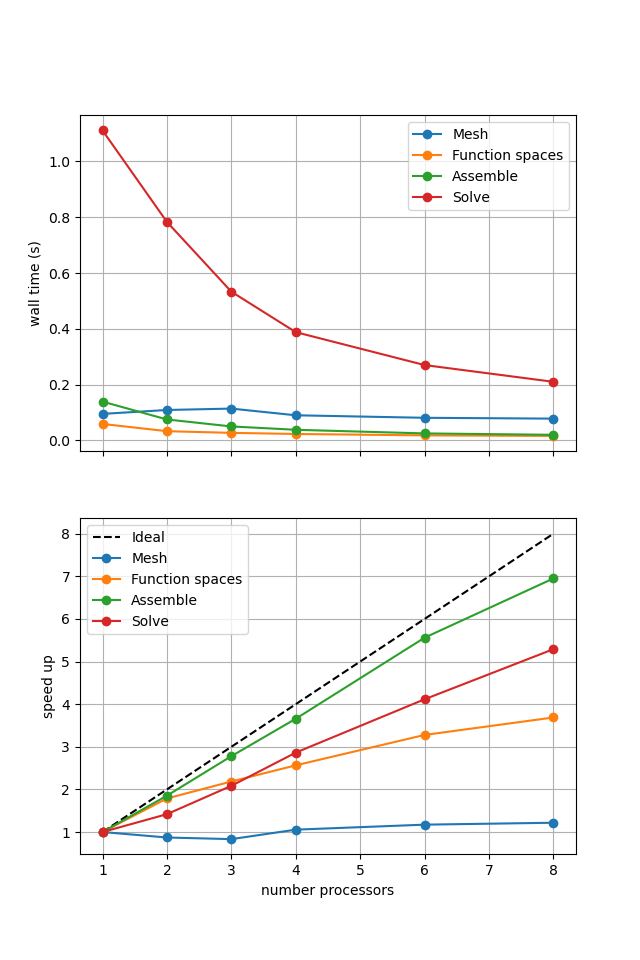

For comparison we provide the output of this notebook using ne = 256, p = 2 and number = 10 in Figure 2.3.1 generated on a dedicated machine using a local conda installation of the software.

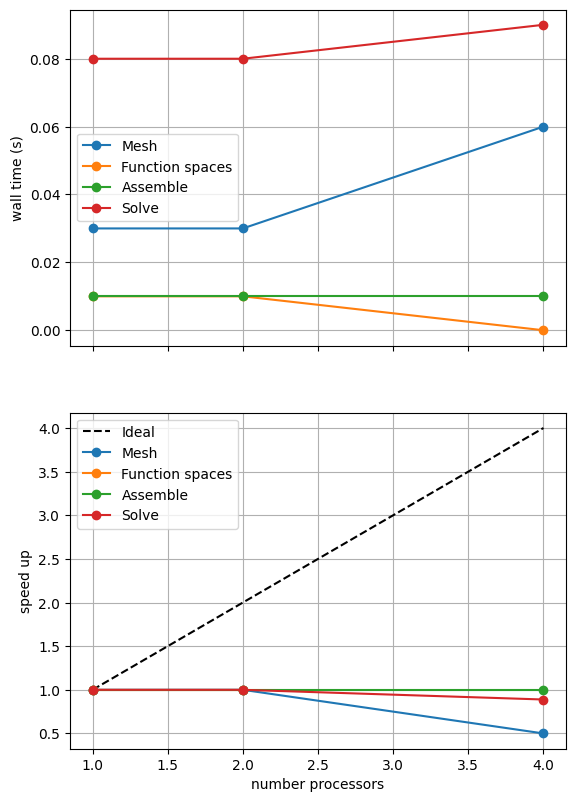

Figure 2.3.1 Scaling results for a direct solver with ne = 256, p = 2 averaged over number = 10 calculations using a local conda installation of the software on a dedicated machine.

Here we can see that assembly and function space declarations scale well, with assembly being almost ideal. However meshing and the solve barely scale at all. The meshing takes place on a single process before being communicated to the other processors, hence we do not expect this step to scale. Additionally the cost (wall time taken) of meshing is so small that it is not a significant factor in these simulations. However the solution step is our most significant cost and would ideally scale. Its failure to do so here is a result of an initial analysis step that is performed by MUMPS in serial (on a single processor), the significance of which will decrease once the solver is used more than once per simulation.

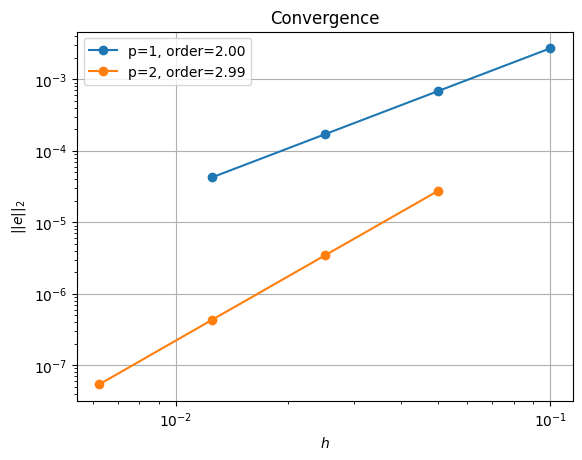

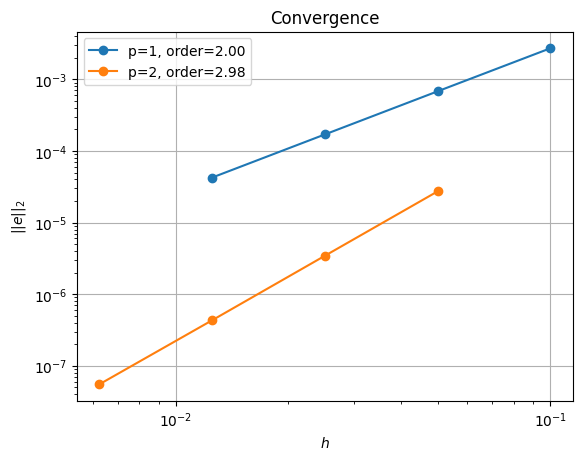

We will try different solution algorithms to get better behavior on a single solve but first we want to check that the solution is still converging in parallel. We do this by running our convergence test from notebooks/02_background/2.3c_poisson_tests.ipynb in parallel using another utility function utils.ipp.run_parallel.

# the list of the number of processors to test the convergence on

nprocs_conv = [2,]

# List of polynomial orders to try

ps = [1, 2]

# List of resolutions to try

nelements = [10, 20, 40, 80]

errors_l2_all = utils.ipp.run_parallel(nprocs_conv, path, 'background.poisson_2d_tests', 'convergence_errors', ps, nelements)

for errors_l2 in errors_l2_all:

test_passes = test_plot_convergence(ps, nelements, errors_l2)

assert(test_passes)

order of accuracy p=1, order=2.00

order of accuracy p=2, order=2.99

Iterative#

Having confirmed that our solution algorithm still converges in parallel we repeat the convergence test using an iterative solver (rather than a direct LU solver). We select a conjugate gradient (CG) iterative solver using a multi-grid (GAMG) preconditioner by passing the petsc_options dictionary to our function. We run over the same list of processors as before.

petsc_options = {'ksp_type' : 'cg', 'ksp_rtol' : 5.e-9, 'pc_type' : 'gamg'}

maxtimes['Iterative'] = utils.ipp.profile_parallel(nprocs_scale, steps, path,

'background.poisson_2d', 'solve_poisson_2d',

ne, p, number=number, petsc_options=petsc_options,

output_filename=output_folder / '2d_poisson_scaling_iterative.png')

=========================

1 2 4

Mesh 0.03 0.04 0.09

Function spaces 0.01 0 0

Assemble 0.01 0.01 0.01

Solve 0.04 0.03 0.03

=========================

*********** profiling figure in output/2d_poisson_scaling_iterative.png

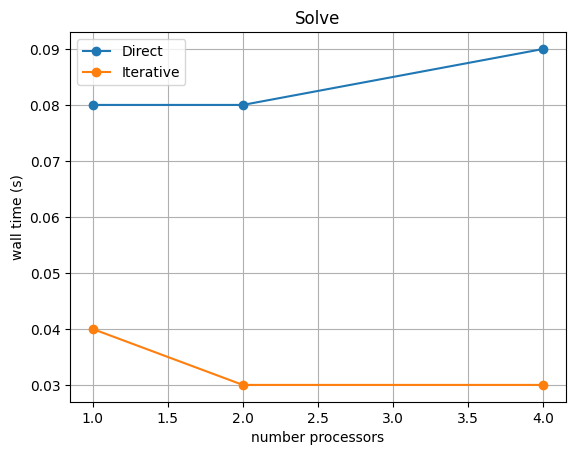

Again, results will depend on the computational resources available when the notebook is run and we intentionally limit the default parameters (nprocs_scale, ne, p and number) for website generation. We can compare against the output of this notebook using ne = 256, p = 2 and number = 10 in Figure 2.3.2 generated on a dedicated machine with a local conda installation of the software.

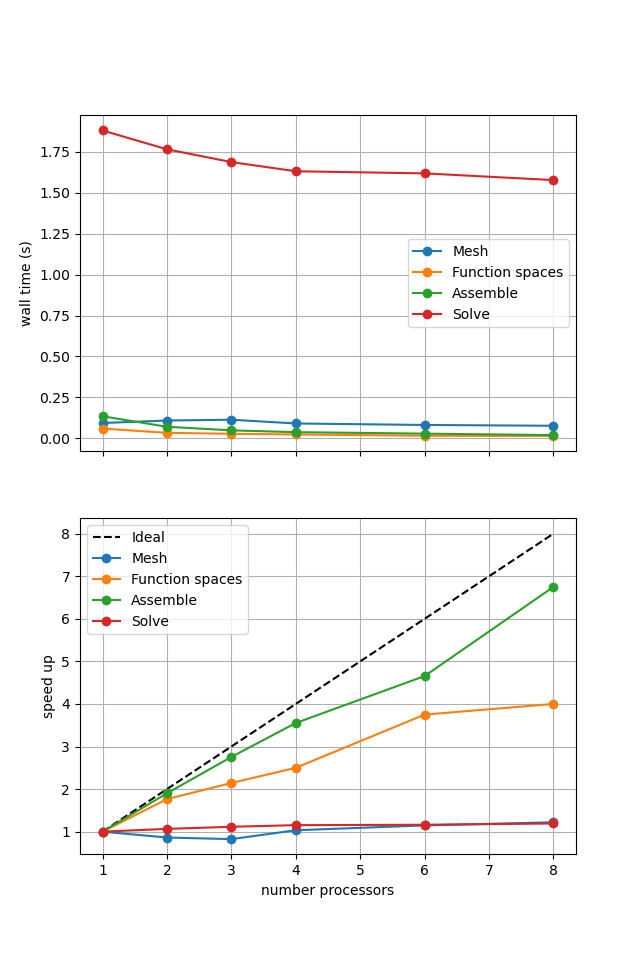

Figure 2.3.2 Scaling results for an iterative solver with ne = 256, p = 2 averaged over number = 10 calculations using a local conda installation of the software on a dedicated machine.

Here we can see that the solution algorithm scales much better than with the direct solver. We also need to check that the model is still converging by running our convergence test from notebooks/02_background/2.3c_poisson_tests.ipynb.

errors_l2_all = utils.ipp.run_parallel(nprocs_conv, path, 'background.poisson_2d_tests', 'convergence_errors', ps, nelements, petsc_options=petsc_options)

for errors_l2 in errors_l2_all:

test_passes = test_plot_convergence(ps, nelements, errors_l2)

assert(test_passes)

order of accuracy p=1, order=2.00

order of accuracy p=2, order=2.98

The iterative solver produces similar convergence results in parallel to the direct method. Note however that we had to set the iterative solver tolerance (ksp_rtol) to a smaller number than the default to achieve this at p = 2 and for small grid sizes (\(h\))/large numbers of elements (ne).

Comparison#

We can compare the wall time of the two solution algorithms directly.

# choose which steps to compare

compare_steps = ['Solve']

# set up a figure for plotting

fig, axs = pl.subplots(nrows=len(compare_steps), figsize=[6.4,4.8*len(compare_steps)], sharex=True)

if len(compare_steps) == 1: axs = [axs]

for i, step in enumerate(compare_steps):

s = steps.index(step)

for name, lmaxtimes in maxtimes.items():

axs[i].plot(nprocs_scale, [t[s] for t in lmaxtimes], 'o-', label=name)

axs[i].set_title(step)

axs[i].legend()

axs[i].set_ylabel('wall time (s)')

axs[i].grid()

axs[-1].set_xlabel('number processors')

# save the figure

fig.savefig(output_folder / '2d_poisson_scaling_comparison.png')

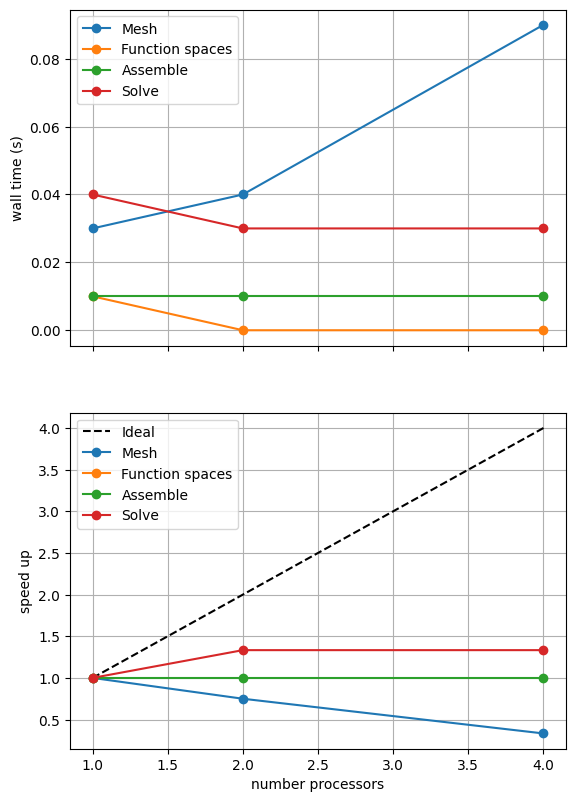

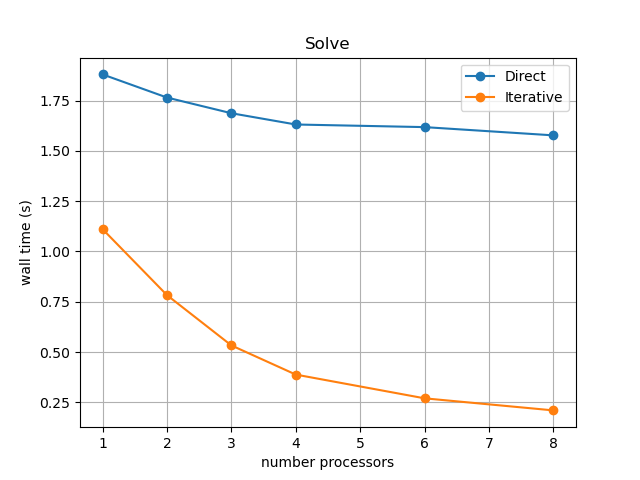

Again, results will depend on the computational resources available when the notebook is run and we intentionally limit the default parameters (nprocs_scale, ne, p and number) for website generation. We can compare against the output of this notebook using ne = 256, p = 2 and number = 10 in Figure 2.3.3 generated on a dedicated machine with a local conda installation of the software.

Figure 2.3.3 Scaling results for an iterative solver with ne = 256, p = 2 averaged over number = 10 calculations using a local conda installation of the software on a dedicated machine.

This emphasizes that not only does the iterative method continue to scale (decreasing wall time) to higher numbers of processors but its overall wall time is also lower than the direct method. We will see that this advantage decreases once more solves are performed in the simulation because the poor behavior of the direct method here is caused by a serial analysis step that, in our examples, only needs to be performed once per simulation.

Next we examine a more complicated case with two solution fields - a cornerflow problem where we are interested in finding both the velocity and pressure.